Toyota HiLux 2024 review: Rogue V-Active - off-road test

The 2024 Toyota HiLux represents a small step in an EV-lite direction. Some new...

Browse over 9,000 car reviews

There was a time when the short-wheelbase versions of the Nissan Patrol (and the majority of its competition) were the big sellers. That’s not the case these days where the long-wheelbase wagon is king, and, in fact, you haven’t been able to buy a short-wheelbase version of the Patrol, Toyota LandCruiser or Mitsubishi Pajero for years.

So how did this layout previously dominate the market? Basically, the SWB wagons ruled because that was about all you could get. Back then, off-road vehicles were very much work vehicles, even if they had a hard or soft top rather than a tray out the back. The mining industry, civil engineering firms, emergency services and farmers were the biggest consumers of off-roaders back in the 1960s, so not a whole lot of thought was given to passenger accommodation or, indeed, passenger comfort.

When Nissan launched the G60 Patrol here in the early 1960s, it was actually available in a long-wheelbase wagon format, but most buyers gravitated to what they were seeing in-service, which was the shorty. It was cheaper and, until camping became the complicated event it is now with gadgets for every task, it did the job space-wise. And just to illustrate how innocent the market was, the soft-top version sold strongly against the vastly more weather-proof and comfortable hard-top.

Those early, G60, Patrol shorties were available with just the one mechanical package, starting with the part-time, two-speed transfer-case, three-speed manual gearbox and a 4.0-litre in-line six-cylinder engine good for a claimed (but probably optimistic) 108kW of power and 319Nm of torque. Suspension was by leaf springs all round and the brakes were four-wheel drums.

The MQ Patrol of 1980 was the real game-changer in a sense, because it came along at a time when the idea of a four-wheel-drive for family fun on the weekends was taking hold. While the SWB MQ sold well, it was the LWB station-wagon that was making headlines and emerging as the alternative to a conventional family car.

In MQ form, the shorty suddenly gained front disc brakes and a four-speed manual gearbox, while the conventional transfer-case set-up and leaf springs remained. The soft-top option was gone by now but, to underline the new marketing direction of vehicles like the MQ, there was a choice of petrol or diesel power. The petrol option was a 2.8-litre version of the SOHC six-cylinder than powered the Datsun 240 and 260Z sporty coupes. In Patrol form it made 88kW and 201Nm and did the job in a fairly understated way. But if you could handle even more straight-line understatement, then the new 3.3-litre diesel brought with it 70kW of power and 215Nm of torque.

Of course, it was the LWB wagon version that was stealing the limelight, a fact proven when it became the Patrol version with the highest (Deluxe) trim level and the only member of the Patrol squad to score the new turbo-diesel engine option when it arrived in 1983, or the option of a three-speed automatic around the same time. Clearly, the SWB versions had become a bit of a side-show.

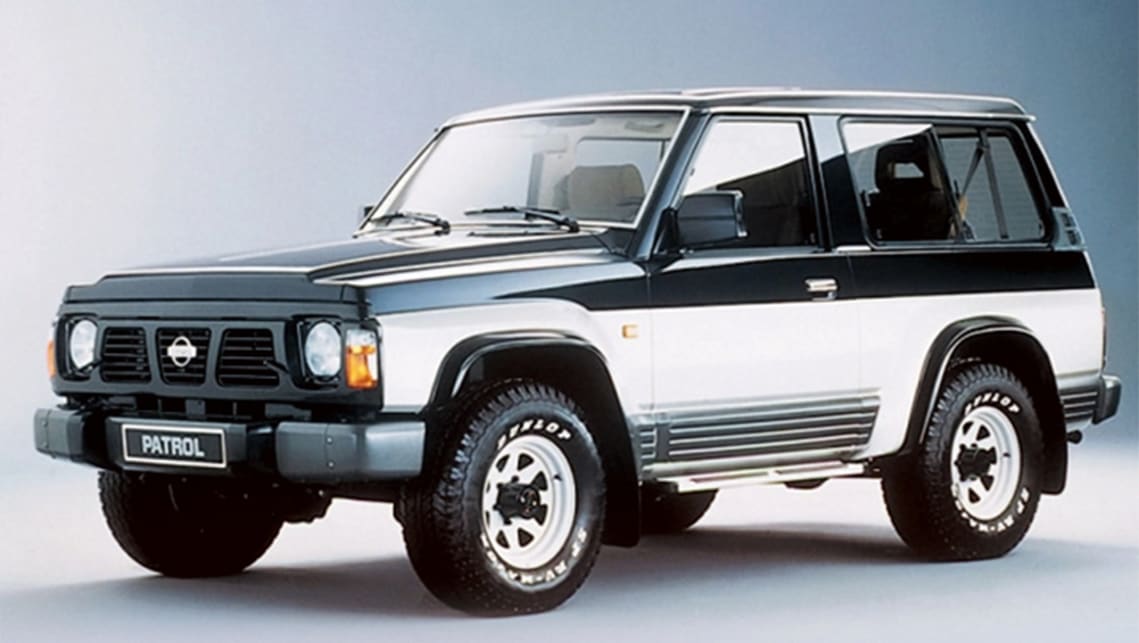

That feeling intensified in 1988 when the all-new GQ Patrol turned up. Yes, you could still buy a SWB Patrol, but the big question was why. Again, though, the rusted-on shorty fans stepped up and quite a few SWB GQs were sold. In GQ form, the SWB was available with the 4.2-litre non-turbo, 85kW/264Nm TD42 4.2-litre diesel with a five-speed manual or the 4.2-litre petrol six with 125kW and 325Nm with either the same manual or a four-speed automatic option. The bigger news, of course, was the GQ’s new coil-sprung suspension at each corner.

And that was about where the evolution of the Patrol SWB finished up.

So what were the problems with a short-wheelbase Patrol (and any other shorty wagon for that matter)?

They start with the fact that there’s just not enough room inside for some owners. The long-travel suspension eats into the load space in terms of the wheel-arches which, in a long-wheelbase vehicle isn’t such a problem purely because there’s more length to work with. To attain any meaningful cargo space, you needed to ditch the rear seat (if the vehicle had one) making the car fundamentally a two-seater. And that didn’t work for everyone, particularly families.

Modern camping must-have like fridges on a slide aren’t always a natural fit in a short-wheelbase wagon and cramming the back full of gear and slamming the doors shut meant that half that gear wound up on the ground when you next opened the rear doors (which were often barn-doors that opened right to the cargo floor. It wasn’t just old-fashioned vehicle packaging at fault here, either; the much more modern, 21st Century Toyota FJ Cruiser suffered the same problems (without the barn doors).

The solution was to fit a roof-rack to your shorty, but these added an easy litre per 100km to the fuel bill, ands that’s before you loaded them up. Alternatively, a trailer was the solution, but that sliced your off-roading ability down the middle, and that was – originally – the whole point of these vehicles.

Another complaint with a short-wheelbase Patrol (and, again, the Nissan was not alone) was that the shorter distance between the axles made the car, particularly a heavily loaded one, feel a lot more flighty on long, downhill descents in low-range. The rear end felt much more likely to overtake the front in such situations, and even once you’re used to it, the feeling never really goes away.

Even on the bitumen at highway speeds, a short-wheelbase Patrol will never be as relaxed and stable as its long-wheelbase stablemate. The steering can feel a bit nervous due to the lack of wheelbase and the ride quality will be poorer than a LWB Patrol as the vehicle pitches and bucks over bumps. The same can be said of the shorty’s off-road demeanour, too, and SWB Patrol owners know all about hanging on tight in the rough stuff.

But it was in that rough stuff that the SWB Patrol could definitely hold its own. It could turn a bit tighter between the trees than a LWB car and physics dictates that it’s simply easier to get a smaller vehicle through tight obstacles than a bigger one. And since the width of the wheel-track was the same as the LWB Patrol, the SWB would still use the same bush-track ruts with equal ease.

Of course, what really killed the short-wheelbase Patrol was that, even though it was popular with a hard-core of fans who valued its more nimble turning circle and tighter dimensions in the scrub, once those buyers had bought their car, there was no ongoing demand. Once everybody who wanted one had one, that was it, it seemed.

Throw in the fact that the short-wheelbase wasn’t significantly cheaper to produce than the long-wheelbase version, and the writing was on the wall. Nissan more or less dropped the SWB Patrol for Australia when it finished production of the GQ, although a very small, as in, a handful, of short-wheelbase GU Patrols (most, if not all, with the 4.8-litre petrol engine) did make it to Australia and are sought-after rarities today. The real heartland for the shorty Patrol then became the Middle East where SWB Patrols with souped up versions of the 4.8-litre petrol six were common sights at motorsport events where horsepower and grip (such as competitive dune-climbing) was king.

The real SWB Patrol wild-card, however, was not even badged as a Patrol or even a Nissan. Back in the late 1980s in Australia, the Button Car Plan was aiming to make the local industry more viable by reducing the number of individual models being built (and developed). So car-makers were being encouraged into joint ventures where development costs would be shared along with the finished product. It didn’t quite work out that way and the industry spiralled downwards into the tacky, expedient world of badge engineering; where one maker takes another’s product, slaps its own badges on and calls it a different car.

In Nissan’s case, a deal with Ford did actually see joint development of the Pintara/Corsair twins respectively, but it also gave us the laughable Ford Falcon utility with Nissan Ute badges and the equally absurd Nissan Patrol with Ford Maverick badges, one variant of which was a petrol or diesel-engined shorty. Oh the shame.

Read more Nissan Patrol advice:

- TD42 engine: Your guide to the Nissan turbo diesel motor

- G60 Patrol: Your guide to the Nissan 4WD

Comments