When it comes to suspension, both the front and rear systems are equally important, unless you enjoy the prospect of your car dragging its rump like a carpet-ruining dog or burying its nose like a truffle pig.

It’s just that the front suspension is more equally important. There’s more load on it under cornering and braking, for instance, and then there’s the little matter of actually steering, which enthusiasts enjoy and the rest of us find pressingly necessary.

Consider that the rear suspension’s job is to do one thing really well, whereas the front suspension is the master of multitasking. Sounds familiar, in a Men Are From Mars… kind of way.

Put simply, front suspension is even more complex than the rear. In all but the rarest of cases, such as the Honda Prelude, which was fitted with four-wheel steering, the rear wheels stay in a fixed position. The front wheels, on the other hand, have to deal with all the road has to offer while offering a full range of motion.

And, in front-wheel-drive and four-wheel-drive vehicles, the front suspension has to keep the engine’s torque from unduly affecting the steering and stability of the car as well.

It takes a decent whack of engineering in order to go around corners

So, as you might imagine, it takes a decent whack of engineering in order to go around corners without your car acting like a 1.5-tonne pinball.

There are two main methods to keep your front wheels in check; each varies in construction, size, complexity and cost, as well as its effectiveness at reacting to high-pressure situations.

Strut-based systems

When we talk about strut-based suspension, we’re really only referring to the most popular and widely used system, the MacPherson strut, which is about as ubiquitous as the Band-Aid brand when it comes to sticky bandages.

Invented in the late 1940s by Earle MacPherson and basically unchanged ever since, the humble McStrut has appeared on everything from city runabouts to Porsche 911s.

The MacPherson system is one of the lightest, simplest, cheapest and most space-efficient ways to keep everything under control, thanks to its method of mounting the suspension strut directly to the body, rather than via a series of control arms, joints and rubber mountings.

MacPherson strut systems provide simple steering pivots at the wheel hub

Now, if you wanted to be entirely pedantic, MacPherson strut systems still use a single control arm, located at the bottom of the assembly, but it’s a far cry from the complex, four- and five-point mounted control arms that adorn wishbone and multi-link systems.

MacPherson strut systems provide simple steering pivots at the wheel hub, allowing the easy connection of steering systems via small metal bars known as tie rods.

Unfortunately, MacPherson struts are unable to allow for vertical movement – during bumps in the road, for instance – without leaning the wheel towards the car as the suspension compresses, and slanting it back out as the system decompresses.

This can cause an unsettling feeling that the car wants to go for a wander, rather than staying in its lane and is known as “bump steer”. While it’s something we put up with in dodgem cars, cancelling it out in road vehicles requires careful engineering work to ensure the suspension and tie rod work together as well as possible.

Because dual wishbone and multilink systems are able to move vertically without pivoting around, it’s much easier for engineers to avoid bump steer all together.

Similarly, because of the MacPherson’s assembly, it’s impossible to adjust a single setting without affecting others in the process. This means that engineers have to strike a compromise that may not provide the ideal foundations for control, agility and stability.

Control arm systems

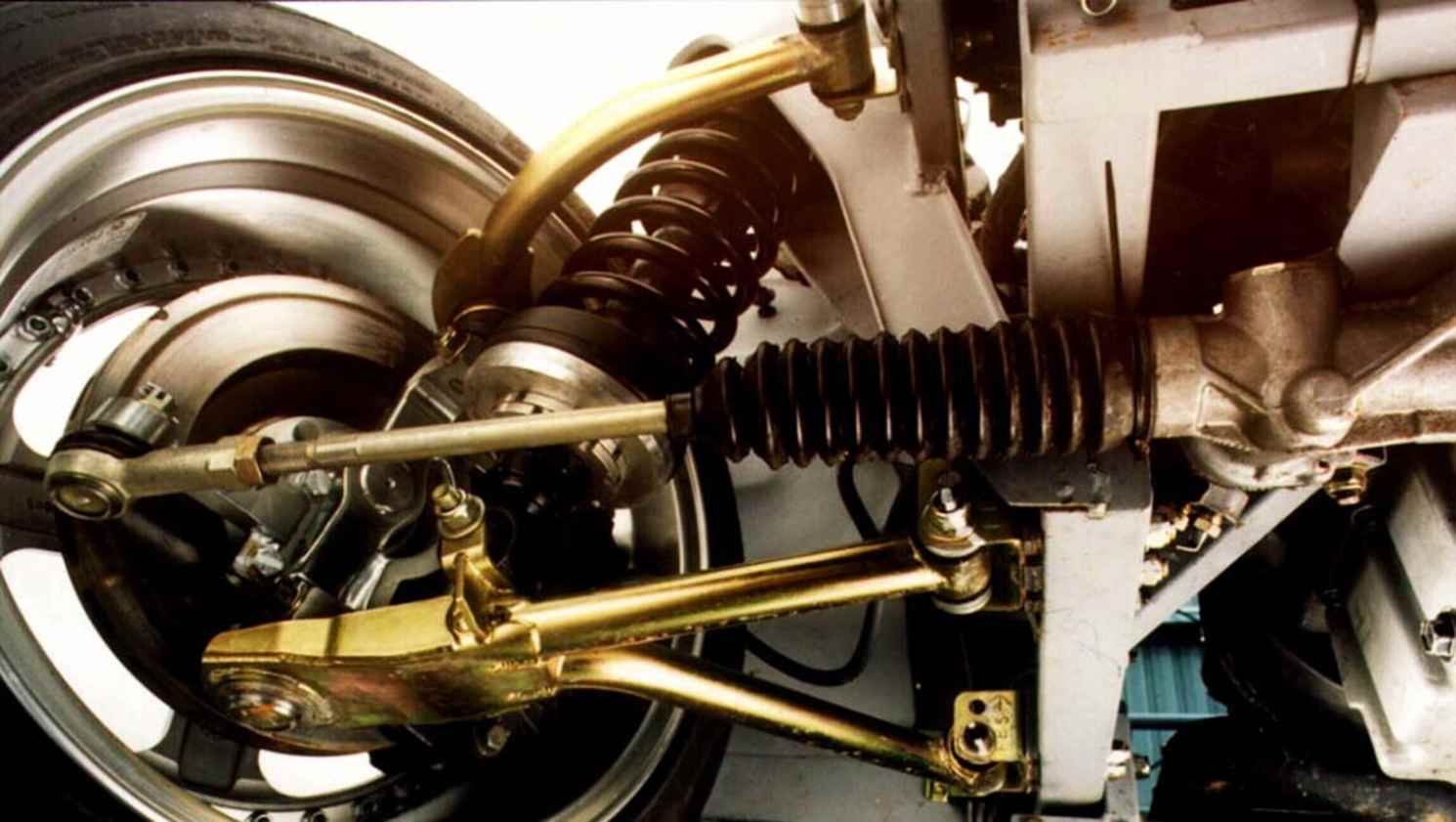

Curing the ails of the MacPherson strut are the modern double wishbone and multi-link systems, wielding multiple control arms in an effort to isolate struts and springs from the car body.

Now, while wishbones can technically be called control arms, control arms aren’t wishbones. Wishbones are named after the little forked bone you snap after a roast chicken, and shaped exactly the same.

This means that each wishbone is mounted on the body in two places, making sure the wheel can’t move back and forward along the length of the car. It can do so without the need for extra mounting points and links to arrest unwanted movement.

Multi-link suspension works in the same fashion as dual wishbones, offering more flexibility in where engineers place the control arms

Control arms, in their narrowest definition, are a single, un-forked piece of metal that attaches to the car body in just one place. Because of this, a simple, one-directional control arm – as found on the MacPherson strut – provides less resistance to front-and-back movement, requiring extra reinforcement from a metal pole known as a radius rod to keep everything where it should be.

That said, if you use enough control arms, you can replicate the fore-and-aft resistance of double wishbones. This setup is known as multi-link suspension and works in the same fashion as dual wishbones, offering more flexibility in where engineers place the control arms, as well as the ability to adjust the suspension characteristics individually.

The principle drawback of this adjustability and flexibility is, of course, the mystifying complexity of dual wishbone and multilink systems. And, as a result, the cost, size and weight skyrocket accordingly.

Control arm systems take up a lot of horizontal space, leaving less for engine, gearbox and steering components. It’s a struggle to try and wedge all the necessary oily bits into an engine bay at the best of times, without suspension components annexing the space. With the current trend of downsized engines, however, it should pose less of a problem.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)